Why the Right Targets Are Important in Bacterial Vaginosis Testing

NAAT, with its ability to deliver accurate diagnoses, can help patients with bacterial vaginosis get the treatment they need.

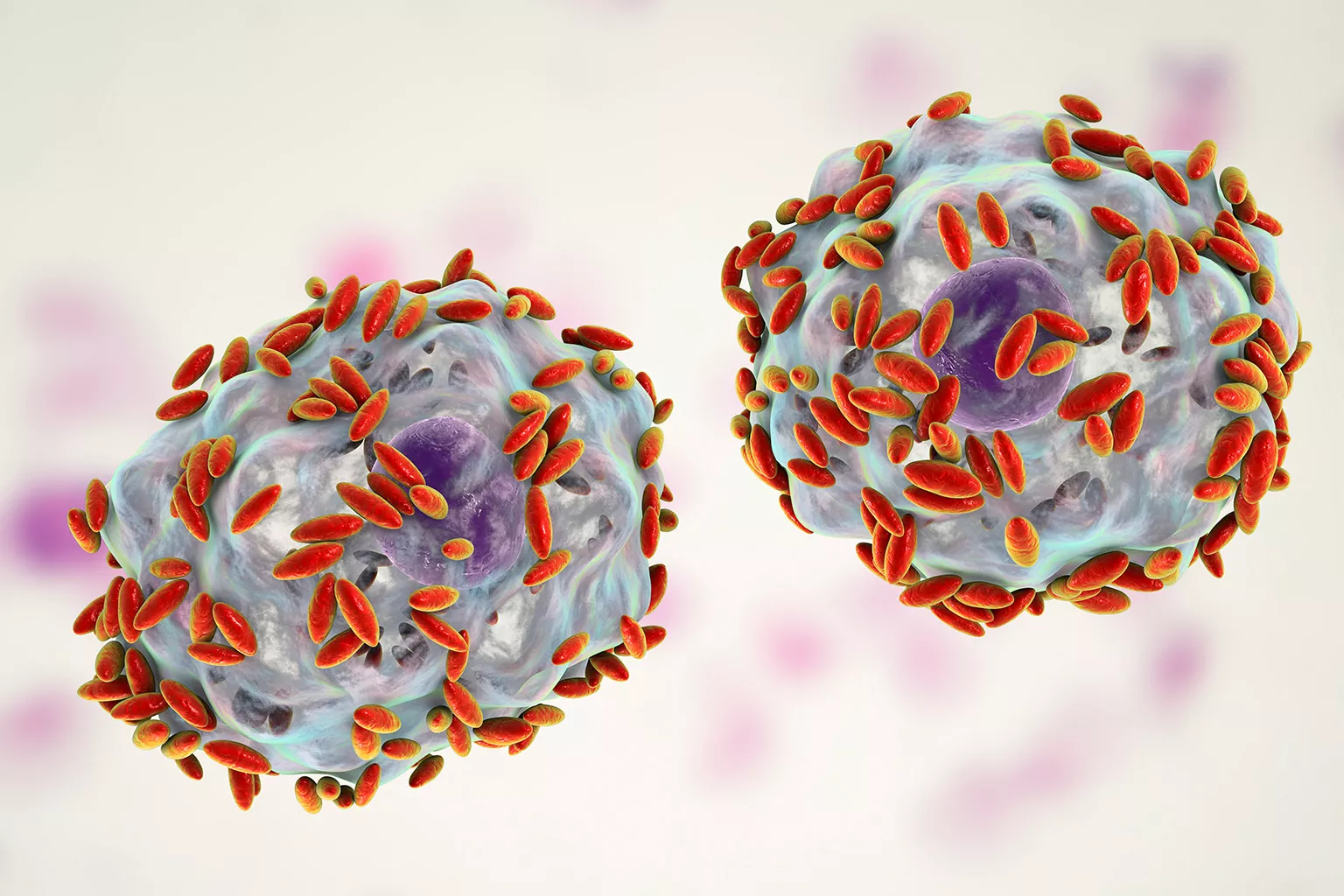

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common vaginal condition that affects over 20 million women in the United States, mainly those between 14 and 49 years of age.1,2 This condition is not caused by a specific parasite or fungus (such as Trichomonas vaginalis or yeast, respectively),3,4 but occurs as a result of an imbalance in the vagina’s natural flora.5 A healthy vagina has a bacterial ecosystem with a pH between 3.8 and 5.0 (which is moderately acidic) and consists of over 200 species of bacteria and fungi.6,7 Lactobacillus is the dominant microbe in a healthy vaginal ecosystem and produces various antimicrobial compounds. A loss or decline in the total number of Lactobacillus, along with an increase in the concentration of anaerobic microbes, together characterize BV.8

Lactobacilli, which are Gram-positive bacilli that can prevent the propagation of anaerobic bacteria, play an important role in keeping the vaginal environment healthy.9 Problems arise once an imbalance in the flora occurs and results in an overgrowth of pathogenic microorganisms.5,10 This leads to the pH increasing to greater than 4.5,7 making the vaginal ecosystem more hospitable to the growth of harmful bacteria, such as Gardnerella vaginalis (G. vaginalis) and Atopobium vaginae (A. vaginae) that are already naturally present in the vaginal ecosystem.11-13

More about these bacteria and how they disrupt normal vaginal flora and the Lactobacillus population:

G. vaginalis was discovered in 1955 and was once considered to be BV, but research has demonstrated that it is only a factor, albeit a key one, in development of BV and is present in almost all patients diagnosed with BV.11,14 As levels of this microorganism rise to unhealthy levels, patients may experience vaginal fluids that are off color (off-white, gray, or green) and malodorous (especially post sex or during a patient’s period).13 This is due to increased levels of G. vaginalis providing a platform for other forms of bacteria to bind to it and flourish.13

A. vaginae, a Gram-positive bacterium only recently associated with BV, exists in very low levels in healthy vaginal fluid. It rarely occurs without G. vaginalis and is estimated to be a factor in 80% of BV cases and may influence treatment success, resulting in recurrences of BV.12,15

The bacterial imbalance that leads to BV can be caused by douching, lack of condom use, or having new or multiple sex partners.5 Most women (84%) with BV demonstrate no symptoms,1 but those that do may experience discolored vaginal discharge, itching/burning in the vagina, malodor especially post sex, and burning during urination.16 If left untreated, women may experience urinary tract infections, chronic pelvic pain, and increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).17 In patients who are pregnant, untreated BV can result in adverse pregnancy outcomes, including postpartum endometritis (infection of the uterus or upper genital tract).18

Traditional BV diagnostic methods

There are several methods that can be used to diagnose BV. The traditional diagnostic methods include Nugent scoring system, Amsel’s criteria, and DNA probe test:5,19

- Nugent scoring entails the microscopic evaluation of vaginal samples where a value is assigned to three different bacterial morphotypes (Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, and Mobiluncus [curved bacteria]) seen on a Gram stain.20 As mentioned previously, Lactobacillus is a good bacteria that promotes vaginal health and Gardnerella can be detrimental to vaginal health. Mobiluncus is an anaerobic, Gram-variable bacillus that also negatively impacts vaginal health and has been reported in 40-60% of patients with BV. 21,22 These three bacterial morphotypes are scored on a scale of 0-10, where higher scores indicate greater presence of bacteria, and a score of 7-10 represents a positive identification of BV.17

- Amsel’s criteria uses a vaginal swab of discharge, microscope and slide/wet prep, and potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution. A positive diagnosis for BV is determined if a patient has at least three of these four criteria: 1) homogeneous, thin discharge that coats the vaginal walls; 2) more than 20% clue cells on saline microscopy; 3) vaginal fluid pH greater than 4.5; and 4) positive KOH whiff test result.5,23

- DNA probe directly detects nucleic acids from G. vaginalis, Candida species, and T. vaginalis, but without target amplification prior to detection.24 DNA probe can detect the three main causes of vaginitis (G. vaginalis, Candida species, and T. vaginalis); however, for BV specifically, DNA probe only detects G. vaginalis, which is prevalent in 70% of women without BV–resulting in overcalling and false positives.24-26 Neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) nor American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently support use of DNA probe for the diagnosis of BV.18,27

The value of nucleic acid amplification testing

An emerging method for BV diagnosis is nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) which allows for simultaneous investigation of multiple targets indicative of vaginal infection.28,29 Although there are many diagnostic methods available, NAATs show advantages in accuracy.30 These tests detect specific bacterial nucleic acids and have high sensitivity and specificity for G. vaginalis and A. vaginae, as well as the good bacteria Lactobacillus.18,28,29 Results can usually be available within 24 hours.5 The Aptima® BV assay from Hologic amplifies nucleic acid from Lactobacillus, G. vaginalis, and A. vaginae and was designed with easy-to-interpret qualitative results from highly sensitive quantitative detection.

The Aptima® BV assay utilizes an advanced algorithm that compares ‘good’ bacteria to G. vaginalis and A. vaginae to determine the imbalance in flora associated with BV. This assay provides a single, objective result with a sensitivity of 95.0%-97.3% and a specificity of 85.8%-89.6%.31 Compared with other testing methods, NAATs can detect three times more mixed infection cases than clinical diagnosis with wet mount, culture, and Amsel’s criteria, and can also detect mixed infections more frequently than clinical evaluation or DNA probe testing.32 Another advantage of NAAT is the option to use patient-collected swabs for specimen collection.29,33

BV is a vaginal infection that if left untreated has the potential for serious consequences in women. Testing methods with high sensitivity and specificity for the bacteria that cause BV are vital to provide an accurate diagnosis and the initiation of proper treatment. NAAT is able to provide accuracy in BV detection by targeting Lactobacillus, G. vaginalis, and A. vaginae, and has the ability to detect more positive samples than Amsel’s criteria, Nugent scoring, or DNA probe.17,32 The Aptima® BV assay, by evaluating the amount of both good and bad bacteria within the vaginal flora, can provide healthcare professionals with an increased accuracy of diagnosing BV and can help to protect female patients’ sexual health.